In this series of blog posts James and Charlotte are going to be looking at some of the interesting projects and developments that have occurred in Hull during the twentieth century as a means to stimulate debate around the urban history of Hull. This first post concerns arguably Hull Corporation’s first really bold scheme to recognisably constitute ‘urban redevelopment’ – as the term came to be used in the later part of the twentieth century – the interwar efforts to redevelop Ferensway into a landmark municipal centre and symbol of Hull’s vibrant future.

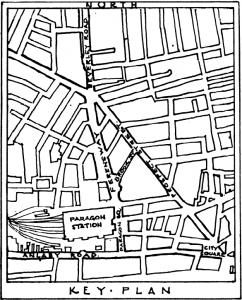

Almost exactly 90 years ago on the 17th October 1931 Hull Corporation held a grand pageant to inaugurate one of the most ambitious urban redevelopment projects of its era, the creation of Ferensway. Presided over by Sir Granville Ryrie, High Commissioner for Australia, the project according to The Times marked ‘an advance in municipal architecture and municipal development’ and represented ‘one of the finest [thoroughfares] in the North of England’.[1] Hull Corporation’s Ferensway project — a plan for a new city centre boulevard, complete with shopping arcades and car parking — although never wholly completed, was authorised under the provisions of the Kingston-upon-Hull Corporation Act, 1924. The land for the Ferensway project had been gradually acquired from 1914 to 1929 and the new development occupied an area formerly composed of cramped slums and small factories, which had been cleared to make way for the new development. Indeed, whilst the creation of Ferensway demonstrated the ebullient civic pride and considerable resources of local government in Hull during the interwar period, the building of small houses at low rents to rehouse the inhabitants displaced by the project also signalled the willingness of Hull Corporation to involve itself in the more mundane, yet equally important business of social housing.

Named after Hull philanthropist, local politician and businessman Thomas Ferens, who had died in 1930, the Corporation held a competition to design all the buildings on the new route, where care was taken to ensure good traffic flows, uniformity of design and even specially devised lighting that would create a cheerful atmosphere.[2] Wesley Dougill ,writing in the Town Planning Review in 1934, was enthused by the ‘special attention’ paid to the need for ‘a unified architectural treatment for the facades of the whole street’ that had flowed from the winning designs of London architects Scarlett and Ashworth. The Corporation and the emerging exponents of the relatively new art of urban planning hoped that the scheme would be a landmark in municipal redevelopment. Yet, despite the early progress and fanfare, the project ground to a halt towards the end of the 1930s and many of the grand buildings were never achieved. Yet its importance lies in showing us two things. First, it shows just how confident and vibrant Hull’s sense of municipal pride was in this period, a facet of local identity that Mike Reeve has shown in his own examination of the opening of the new ‘Joint Dock’ in 1914.[3] Second, it illustrates an ambition to control and acquire land on a large scale that would be in even greater evidence after the war, a process that would reach its culmination in Abercrombie and Lutyens Plans for the post-war city. Ferensway, if the project had been completed, would have been lined with Neo-Georgian frontages and would become the ‘pivotal centre’ of the Corporation’s ‘bold and many-sided scheme of reconstruction’ that included slum clearance, garden suburbs, twelve miles of new roads, bridges and ‘the conversion of an obsolete block into a beautiful boulevard.[4] The project thus represented an ambition for the Corporation to do more than building fine buildings and beautiful boulevards. It showed a desire to take control of the destiny of the city and to shape the future lives of its inhabitants in a more holistic sense than had ever been attempted in Britain before. In Hull though, as in almost every other city where similar ambitions were beginning to take root, the plans never entirely came to fruition. Governments and finances changed and the fortunes and priorities of the city waxed and waned until the Ferensway project was abandoned.

[1] The Times, ‘News in Brief’ 16 Oct 1931, p.11 & ‘Pageant of Transport in Hull’, 19 Oct 1931, p.9

[2] Wesley Dougill, ‘Urban improvement schemes: ii. Ferensway, Hull’, The Town Planning Review, 16:2 (1934), 123-125.

[3] Michael Reeve ‘An Empire Dock’: Place Promotion and the Local Acculturation of Imperial Discourse in ‘Britain’s Third Port’, Northern History, 58:1 (2021) pp.129-150.

[4] David Neave and Susan Neave, Hull (London, 2012), p.24

Aspects of this post appear in James’ book Reconstructing Modernity (Manchester University Press, 2018)