In this blog post our project leader Dr James Greenhalgh explores more findings from our ‘walking workshops’ and interrogates the notion of Hull as a ‘forgotten city’ – referred to only as a ‘North East Coast Town’ and eclipsed from popular memory of the Second World War.

Of all the memories and points of interest that featured in our walk around Hull with the volunteers at the end of November, nothing was more prominent than the legacy of the Blitz in Hull. Bombed or rebuilt buildings proved to be talking points and memory-joggers and many of our participants were keen to expand upon the associations between Hull’s post-war fortunes and their own lives at the Hull History Centre afterwards. No doubt the richness of their responses to this aspect of Hull’s past was in part due to our stated interest in the post-war history of the city. The people who we met rightly expected that we would be interested in local memories and stories associated with bombing and reconstruction, and duly obliged with a wealth of narrative rooted in the landmarks of Hull’s pre- and post-war architecture.

In this blog we are going to focus on one aspect that frequently came-up and, indeed, comes up time and again in the narrative of Hull’s Blitz: the notion that Hull was excluded from the post-war memory of the Blitz on Britain. In particular we are going to look at the idea that the excision of Hull from Britain’s national ‘Blitz story’ is tied-up with the city only ever being referred to as a ‘North East Coast Town’ and why this might be important for our project.

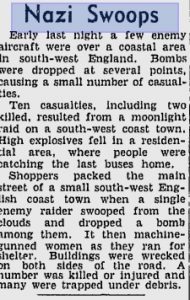

That Hull was repeatedly referred to in both national and local press coverage of bombing as a ‘North East Coast Town’, rather than by name, is certainly true, Indeed, it is easily verifiable with a look through newspapers from the time, and the below extract here from the Shields Evening News from 14th July 1943 shows one of many examples. Tom Geraghty further highlighted this rather unwieldy name in the title of his 1951 work on the Hull Blitz North East Coast Town – Ordeal and Triumph: Story of Kingston-Upon-Hull in the 1939-45 Great War.[1] In doing so, Geraghty both demonstrated the persistence of the feeling in Hull that the city had been overlooked and enshrined the phrase in print.

Shields Evening News, 14 Jul 1943

In the twenty-first century the Imperial War Museum’s own website suggests that the lack of Hull’s name in the daily news led to little awareness concerning the severity of the Blitz outside the city, although using a slightly different form of the pseudonym:

For security reasons, news reports on air raids usually referred to Hull not by name but as a ‘north east town’. This meant that many people were unaware how badly the town suffered in the Blitz. [2]

In the aftermath of the war, given the comparatively severe and persistent bombing of the city, this association between the way Hull’s experience was reported and a lack of attention paid to Hull in narratives of the Blitz seems to have coalesced into a point of contention. As one of our volunteers offered: ‘they ignored us when the Blitz was on and they’ve never bothered with us since’. The Hull Daily Mail repeated this idea in 2018, telling readers that, during the Blitz:

…reporting restrictions meant that a bare minimum of news reached the public and Hull was often referred to as just “a North East Coast Town.” It wasn’t until 1947, when the Hull Daily Mail ran a series of articles on the effect of the Blitz on the city, that people outside Hull were made aware of the true extent of this dark period in the city’s history. Even today, however, the role of the city is often downplayed nationally and was left out of a BBC documentary last year.[3]

Ignoring the rather self-aggrandising claim from the HDM – how would publication in the local paper make people outside of Hull aware of the Blitz? – this claim encapsulates the issue. The contention runs that, despite being either the second most bombed city outside of London or ‘pound-for-pound’ the most heavily bombed city’ (or similar), because reporting restrictions at the time meant the city went unnamed, Hull was written-out or forgotten in the story of the Blitz, an omissions that remains to this day.

There are, however, a number of problems with this narrative. It is certainly true that Hull has not featured prominently in popular memories of the Blitz, which as many historians have noted, present an increasingly un-nuanced, heavily stereotyped and highly inaccurate picture of the Blitz, focused principally on London’s east-end communities. Yet, this neglect is also true for most of Britain’s bombed provincial cities. Moreover reporting and naming restrictions concerning Hull were not unusually strict or exceptional. The practice of not naming bombed locations was largely a standard practice, except for London and for a few severe cases. The most notable of the exceptions being the similarly well-remembered case of Coventry, where the Ministry of Information deemed that the city should be named to illustrate Nazi brutality, especially aimed at American audiences. Even where cities were not named, the name could be revealed 28 days later, although the precise date would then not be given.[4] A city like Manchester might thus be reported to be a ‘north west town’ or Exeter might be a ‘south west coast town’. The featured extract from The Age newspaper (below) from 15th February 1943 uses several different formulations of the latter phrase.

The Age, 15 Feb 1943

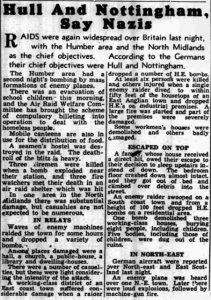

Despite this practice, the public never lacked knowledge of where was being bombed nor how severely cities had been hit. Newspapers were, much to the consternation of the Ministry of Information, savvy in making clear what locations had been bombed without breaching the censorship rules. In the attached extract from the Shields Evening News (above) the report that a North East Coast town has been bombed was accompanied by the judiciously placed addendum that the ‘Germans say Hull’. Similarly, whilst reporting that raids had taken place over the ‘Humber area and the North Midlands’ the Aberdeen Evening Express headlined the article ‘Hull and Nottingham, Say Nazis’ (below) leaving little doubt exactly where the bombing had occurred, even in far-flung Aberdeen. Even so, as historian Juliet Gardiner detailed just as in Hull, people in ‘Birmingham… Bristol, Liverpool and even Ramsgate, felt that it was invariably the London blitz that was given most attention by the media…whilst the rest of the nation took the usual back seat.’[5]

Aberdeen Evening Express, 9 May 1941

The question is, then, why has this conflation of being forgotten and the use of ‘North East Coast Town’ stuck so firmly in local memory if it was nothing unusual. It has certainly not remained part of the lore of other cities that were similarly treated in the press and also heavily bombed. Part of the reason is, of course, the comparatively frequent bombing Hull received and the relative density of the damage for a fairly small city. In 2011, when the façade of the Blitzed National Picture Theatre on Beverly Road was listed, English Heritage’s Maddy Jago claimed that: ‘Together with London, Hull was the most heavily bombed city in the UK, with 95% of its houses damaged.’[6] In 2015 a Yorkshire Post article claimed that ‘Hull was the most devastated city in the UK per square mile – even more than London – but a Government notice preventing its naming for reasons of national security was only lifted in the 1970s.’[7] These types of claims are illustrative of the sentiment felt in Hull, but are rather vague if not wholly inaccurate. There was certainly no formal restriction on discussing bomb damage after the war and the figure of 95% for houses damaged is often cited, but there is little evidence to show that this is accurate nor – more importantly – what such a figure would really mean. There were indeed hundreds of thousands of recorded instances of damage occurring in Hull, but these are not necessarily all different buildings and took place over a period covering the entire war. ‘Minor damage’ – the only figure high enough in the Corporation records to account for the 95% statistic – means ‘any damage at all’, which could include something as innocuous as a few slates or a windowpane. In addition, that Hull was the most bombed city for its size, may or may not be true, but there is no agreed upon measure for such a claim. It was certainly not the city with the highest acreage of damage, or the greatest acreage compared to either size or population. Even given these different measures, there is no agreement on how ‘the most bombed city’ might be defined.[8] There are multiple issues: measurements of what constitutes the area of a city are not uniform; defining ‘heavily bombed’ could mean tonnage or numbers of bombs, buildings damaged or destroyed, hours of raids, expense of restoring facilities, deaths or perhaps some weighted combination of all of these. Even then, figures vary between sources and even departments within Hull’s own corporation disagreed on the impact of raids at a time of incomparable chaos and disruption. If one counts by hand the reports of the Emergency Committee in Hull and compares them to the excellent work done in some of the existing literature, it is possible to say with some certainty that Hull suffered around 82 raids[9], with approximately 4,000 – 5000 of its 92,660 homes damaged beyond repair and 1200 deaths.[10] Moreover, what we can confidently state is that Hull suffered very significant and very visible damage to its central infrastructure, that had an equally significant impact on the local mood. As Mass Observation noted in their 1941 reports on Hull, the raids of June that year had resulted in damage to the business and shopping districts of the city that was more intense than similar locations in the West of London and had tested local morale, if only temporarily.[11]

Given the context of raids in Hull – frequent, several very heavy and lots of visible damage – it is easy to see where the idea that Hull was the worst bombed city by area comes from. As we have already noted, precise information on bombing was scarce at the time and few people would have sat down in the post-war and picked through statistical data. A much larger city like Manchester, for comparison, escaped with a smaller amount of damage, suffering approximately 44 raids, about 680 deaths and had 2000 of its far larger stock of houses recorded by the Corporation as damaged beyond repair. Indeed, several other big cities escaped with comparatively light damage.[12] Put in this context, Hull’s displeasure at being ignored becomes somewhat clearer; it had suffered greater damage than more famous counterparts, yet was still receiving little attention. Yet, there are issues here too. Birmingham, although around three times larger than Hull, claimed that a far greater 12,000 of its houses were destroyed, with 2,200 deaths, whilst contending – although probably based on an accounting mistake – that it was the third most bombed city behind London and Liverpool.[13] Indeed, Liverpool provides us with an object lesson in the similarity of claims made by provincial cities about their Blitz experience. For the ‘Spirit of the Blitz’ exhibition at the Merseyside Maritime Museum in 2003 it was claimed that in Liverpool and surrounding areas over 4,000 people had died and 10,000 homes were destroyed by around 80 raids, that, the museum argued, meant the city was the ‘most heavily bombed British city outside London’.[14] Like Hull, Liverpool harbours a long memory of both the severity of the bombing and its relative lack of coverage in memories of the Blitz compared to the capital city.

The question of why Hull nurtures such a vivid memory of the Blitz and why the associated memory of going formally unrecognised in the media is, on one hand, then, fairly simple. Hull was one of many badly bombed provincial cities that felt unrecognised and continues to do so. Like Liverpool, but also in common with other locations, Hull and its citizens have and continue to reclaim their vital part in the home front and thus the road to victory in the Second World War as a counterpoint to a London-centric narrative of shared sacrifice during the Blitz. In essence, we would find similar stories told in provincial cities across the country, although perhaps not as strongly as in Hull. Given the ubiquity of the Blitz as a prominent aspect of British experience, even in 2022, it is unsurprising that the debate over the relative suffering of each city in comparison to London is constantly reheated.

Yet, for the purposes of this project, the answer is more complex because it takes us past the war and into the treatment of Hull in the post-war period. We need to ask not why Hull resented its exclusion during the war, but rather why it still matters so much. As a number of historians have noted, though Hull hoped that the post-war would bring serious investment in rebuilding, the support it received was, like most places, far from adequate to achieve its ambitions. We’ve talked elsewhere about Hull’s struggles to implement its post-war plan, but that is just one aspect of its post-war struggles. Although few cities received the types of investment they needed after the war and were under-resourced well into the 1960s due to shortages of labour, materials and money, the narrative that Hull was being forgotten again can be seen in the reactions of MPs to the allocations of resources for rebuilding in 1953. In Catherine Flinn’s study of the immediate post-war in Hull, she quotes Richard Law MP for Hull, Haltemprice, responding to what he saw as a lack of funding to rebuild the shopping centre of the city:

…what Hull endured during the war was not generally recognised at the time … Hull endured [air raids] with great patience and fortitude but nobody outside the city knew that it had had anything to bear at all, because, for security reasons, it was not permissible to mention the name of Hull…[15]

For Law it was possible to equate the lack of attention paid to the city during the Blitz, to a more generalised lack of regard for the city as part of Britain nearly a decade later. It is this association, between the disregard of Hull in the war and its continuing marginalisation in a national context that this project seeks to trace.

In 2020 a study suggested that the cities that, like Hull, had suffered the heaviest bombing were still some of Britain’s most socio-economically challenged areas, although the framers of the study were keen to remind readers that there was no causal link. [16] What the study suggested was that areas that experienced heavy bombing were, due to the objectives of strategic bombing, largely working class, industrial towns that were the centres of either war production or supplies of food and materials. That these towns have suffered severe economic conditions in the post-war is then, rather than a result of bombing, really a facet of post-war economic change. Deindustrialisation, which has hit ports and manufacturing towns alike, has caused unemployment and thus poverty at levels higher than in less industrial areas of the country, which of course were rarely bombed. Over 75 years after the war ended, Hull and cities like it, still suffer from some of the poorest economic and health outcomes according to government statistics.[17]

Establishing how the continuity of this narrative of being ignored takes shape in post-war Hull is central to the project’s objectives because it tells us so much about how Hull’s citizens have framed their experience and life stories as part of the city throughout the post-war period. Compared to the other bombed cities like Manchester (lauded now as the capital city of the ‘Northern Powerhouse’), Birmingham and Liverpool (both having experienced significant central area redevelopment after years of serious neglect) Hull still seems to be rather ignored, even during the City of Culture celebrations. At this early stage, as Michael Howcroft observed in his recent work on contemporary Hull, we might suggest that the prominent position afforded to the ‘North East Coast Town’ is, whilst clearly a memory from the war, also a narrative that functions primarily as a sort of metaphor for the more generalised lack of interest, investment and respect shown to Hull by national governments and the popular perceptions of the rest of the country.

Getting to the bottom of these feelings is the core of the Half Life of the Blitz project and what Hull makes the most fascinating city to study.

[1] Tom Geraghty, North East Coast Town: Ordeal & Triumph: The Story of Kingston-Upon-Hull in the 1939-1945 Great War (Hull, 1951)

[2] https://www.iwm.org.uk/history/the-blitz-around-britain

[3] Mike Covell, Hull Daily Mail 29 Oct 2018, online version https://www.hulldailymail.co.uk/news/history/five-tragedies-hull-blitz-ww2-78134

[4] Juliet Gardiner, The Blitz (London, 2011) pp. 229-230

[5] Gardiner, The Blitz, p.234.

[6] http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/england/humber/6324301.stm

[7] https://www.yorkshirepost.co.uk/news/why-has-bbc-ignored-hulls-suffering-blitz-1813074

[8] Catherine Flinn, Rebuilding Britain’s Bombed Cities (London, 2012) pp.86-87 & 177-178 for acreages of various towns and cities and comparative populations.

[9] What constitutes a ‘raid’ varies from report to report.

[10] Hull History Centre, Air Raid Reports, C TAY (dated throughout the war); Flinn, Rebuilding Britain’s Bombed Cities, pp.191-192; Geraghty, North East Coast Town; Philip Greystone, The Blitz on Hull (1940-45) (York, 1991). Flinn, for example cites c.5,300 houses destroyed based on Hull’s 1950 Central Area Plan, but it is never clear where the corporation got these figures given that their wartime figures were in the 4-4,500 range. It is possible then that there was both underestimation during wartime and overestimation in the post-war.

[11] Brad Beaven and John Griffiths, ‘The blitz, civilian morale and the city: mass-observation and working-class culture in Britain, 1940-41’, Urban History 26:1 (1999), p.79

[12] Greater Manchester Country Records Office, Emergency Committee Vol 3 & 4 (various dates) GB127.Council Minutes/Emergency Committee; Peter J. C. Smith and Neil Richardson, Luftwaffe over Manchester: The Blitz Years 1940-1944 (Radcliffe, 2003).

[13] Gordon Cherry, Birmingham: a study in geography, history, and planning, (Chichester 1994); the third most bombed figure, again is hard to substantiate. Sources often cite: John Ray’s The Night Blitz (London, 1996) p.264, but his figures do not cover the whole war.

[14] https://www.liverpoolmuseums.org.uk/whatson/merseyside-maritime-museum/exhibition/spirit-of-blitz#section–the-exhibition

[15] Flinn, Rebuilding Britain’s Blitzed Cities, p.216.

[16] https://www.schooldash.com/blog-2011.html#20201107

[17] https://fingertips.phe.org.uk/static-reports/health-profiles/2019/e06000010.html?area-name=kingston%20upon%20hull